GeoNotes Cypress Hills and area

These articles are updated periodically as new information becomes available. Articles may also be updated for clarity and correction of any research errors. GeoNotes are available online at SOUTHWESTIAN: Search results for GeoNotes (https://southwestian.blogspot.com).

Topics covered are:

ICE AGE MEGAFAUNA (20,000-10,500 years before present), Southern Saskatchewan and Alberta

ICE AGE PALEO AMERICANS (20,000-8500 years before present) and their origins, Southern Saskatchewan and Alberta

THE BIG THAW OF 17,000 YEARS AGO: the nature of glacial dynamics, and our changing climate

FLORA, FAUNA and Holocene (12,000-present) paleoclimates

THE GREAT SAND HILLS, and the alkali lakes and ponds

The MAPLE CREEK-WHITE VALLEY and EAGLE BUTTE ASTROBLEMES

THE BEARPAW MOUNTAINS and the SWEET GRASS HILLS, MONTANA, and the North American Cordilleran mountain building (orogenic) events

CYPRESS HILLS FORMATION: flora, fauna, and topography before the emergence of the Cypress Hills Plateau

THE CYPRESS HILLS STRATIGRAPHIC SEQUENCE: the significance of the K-T boundary (64 Ma) and a major extinction event

THE YOUNGER DRYAS EVENT: a recent climate disruption and extinction event, and how it may relate to past major and minor extinction events

ICE AGE MEGAFAUNA (20,000-10,500 years before present)

Southern Saskatchewan and Alberta

The last Ice Age megafauna data reveals a sudden disappearance of many animals roughly between 14,000 and 9000 years before present or BP (Fig. 1). From about 14,000 BP (Fig. 2), there has been an anomalous cooling period lasting 2400 years. Cooling periods create unusual climate and ecological changes that can have dramatic effects on the biosphere. The cause of the cooling period is not well understood and is attributed to several terrestrial and cosmological factors. Looking closer at this cooling period, along with the examination of the Greenland ice core date an interesting anomaly became apparent between 12,800-11,600 BP (Fig. 2). This period is known as the Younger Dryas Event (YDE).

There has been much speculation as to what happened around 12,800 years ago, with a wide range of conflicting theories. The most accepted theory is that the YDE was caused by the shutdown of the North Atlantic current that circulates warm tropical waters northward by the sudden influx of cold fresh water from the North American deglaciation. However, in the 1990s, a stronger theory with more evidence emerged when paleo-American Clovis archaeological sites were examined in more detail.

At numerous Clovis archaeological sites, mainly in the US, unusual amounts of magnetic particles and microspherules, rich in the platinum group of elements, nanodiamonds, and other high-temperature carbon materials are found within an organic-rich black mat soil horizon (Fig. 3). Above and within this horizon no megafauna or Clovis artifacts were found. Simultaneously, based on coring lake and marine sediment, and ice samples, a major biomass burning (roughly 9% of Earth’s biomass) occurred over a wide geographical area covering four continents. Researchers are leaning towards this as evidence that a cosmic impactor was responsible for the YDE. This catastrophic impactor has several questionable impact signatures and is believed to be a comet or asteroid which broke into several large fragments that struck the thick ice around the Hudson’s Bay, Great Lakes, and parts of Northern Europe. This impact event was mainly a Northern Hemisphere phenomenon that was experienced globally. Most researchers believe the black mat is derived from the combustion of forests and grasslands, but there are some inconsistencies in the scientific literature as to what produced the organic black mat and the high-temperature particulates and elements within the mat.

Figure

3: An example of a layer of organic black mat at the Younger Dryas

Boundary. Image: Richard Firestone (2019)

Figure

3: An example of a layer of organic black mat at the Younger Dryas

Boundary. Image: Richard Firestone (2019)In 2018, an airborne radar survey revealed a 31 km wide, 300 m deep crater in NNW Greenland, the Hiawatha Crater. It was discovered under the gradually retreating 1 km thick Hiawatha Glacier. Originally, it was thought this impactor caused the YDE, but recent Ar40/Ar39 dating of the shocked zircon yielded an impact date of 58 million years. It’s highly unlikely that this impactor was the cause of the YDE.

The initial high losses of the megafauna and the Clovis culture around 12,800 BP were sudden. The suddenness of the event is seen in the frozen Siberian mammoths, some still containing recognizable undigested vegetation in their stomachs, while other mammoths are buried standing upright in the frozen debris muck. Following the initial catastrophic event, drastic ecological and climate changes occurred along with possible paleo-American over-hunting, eventually eliminating some megafauna genera permanently. To date, the Ice Age mammal extinctions that resulted from the YDE are 37 genera lost in North America (82%) and 54 genera lost in South America (74%). Sub-Saharan Africa (16%), Asia (52%), Europe (59%), and Australasia (71%) have also lost a significant number of megafauna, as shown in closed brackets. Mammals whose genera survived the YDE (e.g., deer, moose, and bison) had also suffered greatly with reduced numbers. An interesting aspect to this is the unexpected, swift arrival of new species of mammals, usually after a major catastrophe, that defies natural evolution by thousands, if not millions, of years, has some researchers perplexed as to where these new arrivals suddenly came from.

The Northern Great Plains grasslands supported an abundance of wildlife, much of which is still recognizable today. As the continental glacier retreated northeastward, the wildlife and paleo-American cultures also moved with the retreating ice.

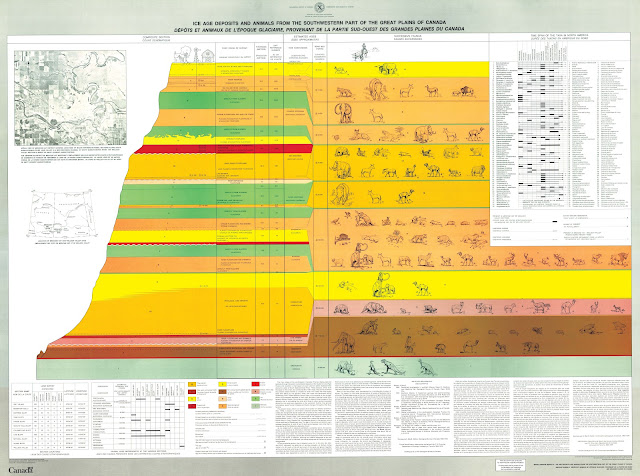

On the southern plains of Saskatchewan and Alberta, Ice Age megafauna discoveries are rare. To get some idea of the kind of mammals that once lived and roamed throughout this area, the remains uncovered from other paleo fauna sites can give important clues. The paleo-fauna covered a wide area, and several of the sites contain the same mammals. Many of the paleo-mammals found at the sites mentioned in this article can be found on a downloadable PDF chart available from the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), mr31_map.eps (canada.ca). A high-resolution jpeg image of the chart can be found at the end of this article.

This article will look at several selected Pleistocene (roughly 126,000 to 11,700 BP, Fig. 4) megafauna sites (Fig. 5) that are mentioned in the scientific literature: Kyle, Saskatchewan; the South Saskatchewan River bluffs near Medicine Hat, Alberta; Wally’s Beach, Alberta; the North Saskatchewan River bluffs near Edmonton, Alberta; and sites along the Milk River and the Missouri Basin in Central and Eastern Montana. The definition of megafauna is an animal weighing more than 40-46 kilograms (88-100lbs). Smaller animals are also mentioned with a focus on the megafauna.

Figure 4: Quaternary period timescale (2018) began with the Laurentide ice sheet, 2.58 million years ago to present. North America is currently enjoying an interglacial period. Abbreviations: “b2k” = before the year 2000. ka = thousands of years before present. Ma = millions of years before present. Image: Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy

Figure 5: Paleo fauna site map. Image: Google Earth

The central, eastern, and northern Montana sites are located in gravel pits of the Milk and Missouri River Basins, which are in pre-Wisconsin (older than 100,000 years, possibly Illinoian glacial or Sangamonian interglacial, see Fig. 6) glacial tills. All Montana sites are chosen arbitrarily and are within 200 km (125 miles) of the Canadian/US border. At Havre, the gravel pits uncovered remains of mammoths (Mammuthus columbi), two species of horse (Equus exelsus and E. Conversidens calobatus or Mexican horse/ass), camel (Camelops minidokae) and mastodon (Mammut americanum). At Saco-Hinsdale, Box Creek, and Red Water Creek sites, mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) remains were uncovered. In the gravels north of Fort Peck near Glasgow and Nashua, horse and mammoth remains were found. South of Fort Peck, remains of bison (Bison occidentalis) have been discovered, and near Lisk Creek, another species of bison (Bison ?latiforns) has been uncovered. In the Wiota gravels at Tiger Butte, SSW of Fort Benton, possibly three species of mammoth (Mammuthus boreus, M. prinigenius, and M. jeffersoni) have been identified. South of Frazer, mammoth and horse remains were discovered in the Wiota gravels. Near Outlook, MT, 11 km south of the Canadian (SK)/US border, tundra muskox (Ovibos moshatus) remains were found, and horse (Equus sp) remains were uncovered in the Lovejoy area, 45 km south of the Canadian (SK)/US border.

Figure 6: The Sangamon interglacial and the Illinoian glacial periods predating the latest Wisconsin glaciation period. Image: GotBooks.MiraCosta.edu.

Other Ice Age mammals some not mentioned at the above sites that likely had their presence in central, eastern, and northern Montana, and up into southern Saskatchewan and central Alberta are; Jefferson’s ground sloth (Meglonyx jeffersonii), dire wolf (Canis dirus), coyote (Canis latrans), grey wolf (Canis lupus), fox (Vulpes sp), bobcat/Lynx (Lynx rufus), scimitar cat (Homotherium serum), badger (Taxidea taxus), long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata), giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), camel (Camelidae hesternus), nearctic deer (Odocoilheus sp), caribou (Rangifer tarandus), pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), bison (Bison bison, B. antiquus and B. occidentalis), mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis), muskox (Bootherium or Symbos), beaver (Castor canadensis), pocket gopher (Thomomys sp), imperial mammoth (Mammuthus imperator), prairie dog (Cynomys sp.), ground squirrel (Spermophilus sp.), Richardson’s ground squirrel (Spermophilus richardsonii), thirteen-lined ground squirrel (Spermophilis tridecemlineatus), muskrat (Ondatra zibethecus), and rabbits (Lepus sp.).

In Alberta, the Edmonton paleo fauna sites are in quarries along the North Saskatchewan River terraces and buried valleys in the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene gravels. Many of the mammalian fauna uncovered are herbivores with a few carnivores, mainly; gray wolf (Canis lupus), giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), and the American lion (Panthera leo atrox). The giant short-faced bear is the first recorded in Alberta. The grey wolf and the American lion have been uncovered previously near Bindloss and Medicine Hat. The herbivores revealed are Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersoni), woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), American mastodon (Mammut americanum), Mexican half-ass (Equus conversidens), Niobrara horse (Equus niobrarensis), barren-ground caribou (Rangifer tarandus, small), steppe bison (Bison priscus), giant bison (Bison latifrons), tundra muskox (Ovibos moschatus), helmeted muskox (Bootherium bombifrons), yesterday’s or western camel (Camelops hesternus), and beaver (Castor canadensis).

An interesting Alberta site, Wally’s Beach 196 km SSE of Calgary, is the only definitive site in North America where paleo Americans (Clovis culture) hunted and processed horses (Equus conversidens) and camels (Camelops hesternus) roughly 13,300 years ago. Also nearby was an unbutchered extinct helmeted muskox (Bootherium bombifrons). Bones of bison, mammoth, and caribou were found along with mammoth tracks on the wind-blown sands.

Another interesting paleo fauna area in Alberta is the South Saskatchewan River bluffs near Medicine Hat where several herbivorous mammals and carnivore remains were uncovered from a buried valley system along the South Saskatchewan River consisting of Pleistocene sand, gravel, silt, and clay deposits of glacial origin. These deposits yielded remains of a sabre-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis), the only confirmed occurrence in Canada. Other cat remains include Lynx (Lynx canadensis), American lion (Panthera atrox), cave lion (Panthera spelaea), giant jaguar (Felis ?atrox), and a scimitar-toothed cat (Homotherium sp.). Scimitar-toothed is a sabre-tooth variant. Herbivores include pronghorn antelopes (Anilocapra americana), bison (Bison bison), western camel (Camelops hesernus), another camel species (Hemiauchenia sp.), Irvingtonian camel (Camelops minidokae), mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis) white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), nearctic deer (Odocoileus sp.) Steven’s long-legged llama? (Tanupolama ?stevensi) reindeer/caribou (Ranifer tarandus), Mexican ass (Equus conversidens), Scotti’s horse (Equus scotti), giant horse (Equus giganteus), southern horse (Amerhippus sp.), stilt-legged ass (Equus calobatus), Siberian mammoths (Mammuthus prinigenius), Imperial mammoth (Mammuthus imperator), Jefferson’s mammoth (Mammuthus jeffersoni), Cook’s mammoth (Mammuthus haroldcooki), ground sloth (Megalonychidae ?Megalonyx sp.) and another species of ground sloth (?Nothrotherium sp.). Also included in the fauna assemblage are wolf (Canis lupus), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), raccoon (Procyon lotor), rabbits (Lagomorpha sp. and Sylvilagus sp.), hare (Lepus townsendii) rodents, and a placental mammal, possibly a sloth (Xenarthra sp.), spruce grouse (Canachites ?canadensis), pocket gopher (Thomomys talpoides), prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), ground squirrel (Citellus ?richardsoni), mole (Microtus sp.), muskrat (Ondatra zibethecus), porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), and mink (Mustela vison).

An interesting Saskatchewan megafauna site near Kyle contains the remains of the most complete skeleton of a mammoth found on the Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba prairies. The 20% complete skeleton was discovered during road construction in 1964. The remains are of a woolly mammoth (the same animal identified differently Mammuthus primigenius [Stoffel,2016] and Mammuthus columbi [Harington, 2017]) and are roughly 12,000 years old. Based on the tusk size, epiphysis (the end of the leg long bone), and molar eruption, it was determined that the animal was a male between 20-25 years old. The animal died of natural causes and showed no signs of being hunted. A detailed study of the mammoth’s bone structure showed a loss of bone density around the vertebrae, indicating malnutrition. Malnutrition is a result of climate change, causing an ecological change that leads to a shortage of food. The paleoenvironmental evidence suggests the area was partly forested with a maximum summer temperature of 28°C.

The difference between the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) and the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius ) is their topographical preference (Fig. 7). Woolly mammoths favour glacial tundra-steppe (this fits the Kyle mammoth) while the Columbian mammoth inhabited savannah environments of temperate southern and central North America. The ranges of both mammoths occasionally overlapped in time and space. A mitochondrial genome study found that both mammoth groups have a nearly indiscernible mitochondrial genome, suggesting interbreeding. This intermediate hybrid may have been the species Mammuthus jeffersonii. The mammoths lived 60-80 years of age, reached heights of 4 m (14’), and weighed 5.4 to 15 tons. Pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis) skeletons have also been discovered on Santa Rosa Island, one of California’s Channel Islands, just off the coast of Santa Barbara/Los Angeles. They reached between 1.4-2.2 m (4.5-7’), and weighed 908 kg (2000 lbs). The last mammoths became extinct on Wrangel Island, Russia, 3750-4000 years ago.

Figure 7: The difference between Mammuthus columbi and Mammuthus primigenius is their topographical preference shown in green. Image: BioMed Central (Physics.org)

Wrangel Island, St. Paul Island (Alaska), and several other islands in the Bearing Strait are remnants of the Bearing Land Bridge that became isolated between 14,700-13,500 BP, trapping the woolly mammoths. These mammoths continued to survive on the islands long after the mainland populations became extinct. St. Paul Island has one of the best-dated prehistoric extinction records. Research indicates that the mammoth's disappearance on St. Paul Island around 5600 BP was triggered by the decline and contamination (urine and feces) of the freshwater supply. Other contributions to the extinction are regional climate change (drier climate 7850-5600 BP), and synergistic effects (e.g. reduced roaming, inbreeding) of a shrinking island as the sea level rose. The vegetation composition on the island remained stable, and there was no human presence, thus not considered to be an extinction factor. Similarly, the Wrangel Island environment was capable of supporting its woolly mammoth population before their extinction; however, to lack of genetic diversity because of inbreeding created a genetic meltdown leading to their demise.

Some animals, like the horse, were eliminated from North America 8000-12,000 years ago, only to be reintroduced much later from Europe by the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1519 when he brought 16 domesticated horses (Equus callabus) to help in the search for his gold. Larger shipments of horses to North America were followed by explorers De Soto and Coronado.

The tundra muskox (Ovibos moschatus) survived YDE and possible paleo-American hunting strategies and is currently inhabiting the extreme Arctic regions of Canada and Greenland. They were reintroduced into Alaska, southern Greenland, Norway, Sweden, eastern Canada, and the Siberian high Arctic. They are also kept in wildlife parks in Germany. The current world population of muskox is between 80,000-125,000 animals. Muskoxen have a thick coat and derive their name from the emission of the male's strong musky odour during mating season to attract females.

The bison (Bison bison) narrowly escaped extinction not from the YDE or the need to hunt by paleo Americans and their modern successors, but by greedy fir merchants and their financiers along with the political chicanery, mainly in the US, to deal with the so-called “Indian problem” of the mid to late 19th century when bison numbers were drastically reduced to 400 individuals. Today, by conservation and careful land management in both the US and Canada, the bison numbers have recovered to more than 500,000 individuals.

Like the bison, the reindeer/caribou (Rangifer tarandus) have survived the YDE and hunting. They inhabit high latitudes, living in the environmentally sensitive colder climates of the Arctic, sub-Arctic, boreal, and mountain ranges of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. In North America and Greenland, the Rangifer tarandus is called caribou, and in Siberia and Europe, reindeer. Since 1998, reindeer/caribou herds have declined on average by 56%. Five herds in Alaska and Canada have shrunk by 90%. Swelling and shrinking of herds is common and not surprising, and so is the changing ecosphere.

The declining reindeer and caribou example can give a clue to past climate-related events affecting the ecosphere and its ability to sustain the biosphere. The cause of the current herd decline is the changing climate. Caribou/reindeer herds subsist on lichen, mainly reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiferina), during the winter months. The reindeer lichen grows on the ground, but warmer temperatures cause taller vegetation to grow, squeezing out the lichen. There are more bugs during warmer weather, causing caribou/reindeer to spend their energy hiding from the insects and not looking for food. Warmer winters create more rainfall, and when it freezes, the layer of ground ice makes it difficult for reindeer/caribou to break through the ice crust to reach the lichen. As a result, large numbers of caribou/reindeer starve to death. In Russia, in 2013, ice cover lichen caused the death of 61,000 reindeer.

Additional information on the caribou/reindeer, the females are the only deer members (Cervidae) that carry antlers. The antlers are used to scrape away snow to uncover lichen and for protection. The fir on the feet is exceptionally long and acts as a thread beneath the hoofs. The feet are wide and act as snowshoes. The males weigh 70-150 kg (154-330 lbs) and the females weigh somewhat less. Reindeer/caribou live to 10-15 years of age and have been around for roughly 770,000 years.

Yesterday’s camel (Camelops hesternus)was slightly larger than today’s camels, had a single hump, long limbs, two toes, and strong lips to grasp food. No camel remains were found east of the Mississippi River, only in the drier open spaces of the central and western Great Plains. They are often found at sites with horse and bison remains. Camels weighed 800 kg (1764 lb). They began their existence in North America 45 million years ago and went extinct around 11,000 BP.

The sabre-toothed tiger (Smilodon fatalis) was a predator on the grassland of the Great Plains and open woodlands. It’s not a true tiger and is only distantly related to modern lions, cheetahs, and tigers. The cat had a thick neck, broad chest, muscular body, thick legs, short tail, and large 17 to 30 cm (7 to 12 inches) long curved canine teeth (Fig. 8). The teeth were used for slicing the jugular vein and windpipe of its prey. Deer, horses, camels, bison, and young mammoths were favourite food sources. Skull wounds of paleo American people suggest that the animal occasionally hunted humans. The animal was an ambush predator that waited for its meal undercover. The cat had a weak bite force, 1/3 that of a lion. Its jaw can stretch 120 degrees, twice that of a lion. The horseshoe-shaped hyoid bone in the mouth suggests it roared. They had no natural enemies but competed for food with other cats and canines. Their life span was around 20-40 years, and the animal weighed between 68-300 kg (150-660 lbs). They went extinct roughly 10,000 years ago and were found throughout the Pleistocene. Different species of Smilodon lived in South, Central, and North America.

Figure 8: The sabre-toothed tiger (Smilodon fatalis). Characteristic large 17 to 30 cm (7 to 12 inches) long curved canine teeth. Image: Dantheman9758, Deviant Art

Muskox distribution in the high Arctic. Red represents the historical habitat. Blue is the introduced population. Image: Wikipedia-Muskox

The shaded area is the North American distribution of the sabre-toothed tiger (Smilodon fatalis). Image: Ashley Reynolds; et al (2019)

Difference between a mammoth and a mastodon. Mammoths are more delicately built, head and shoulders much above hindquarters, high-domes skull, tusks curve down more than in mastodons. Mastodons are stockier with heavy frame, head slightly above hindquarters, low-domed skull, tusks curve down slightly before curving out. Image: Dantheman9758, Deviant Art

Mastodon (browsers) molar on the left has cone-shaped cusps for crushing twigs, leaves, and branches. The mammoth (grazers) molar is ridged for grinding grass, twigs, and leaves similar to a modern elephant. Image: Royal Alberta Museum (Youtube)

Wind scoured mammoth tracks on Wally's Beach at St. Mary Reservoir, Southwestern Alberta. Image: Shayne Tolman from Retroactive.

Size comparison of mammoths, elephants, and a mastodon with a human figure. Image: Prehistory Wildlife

Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) distribution during the Late Pleistocene based on fossil evidence. Siberia and Alaska were connected by the Beringia land bridge. Image: Andy Fyon

A high-resolution image of ice age animals from the southwestern great plains. A downloadable PDF chart is available from the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), mr31_map.eps (canada.ca).

If you planning to do your own research, the radiocarbon (14C years before the present or BP) dates need to be converted to calendar years before the present. Below is a chart and a table to help with the conversion. Usually, the researcher will indicate which dating system they are using. If it’s years before present (for example, 5000 BP) there is no need to convert, if it’s 5000 14C BP or radiocarbon dates BP then a conversion is needed.

An example, the 10,000 radiocarbon date (vertical axis) is roughly 11,400 calendar years (horizontal axis) on the squiggly line. Or, you can also use the chart below to get the calendar years before the present.

Sources:

A Pleistocene Wonderland; Montana Department of Transportation; Helena, MT; Site accessed 5-16-2022; PleistoceneWonder.pdf (mt.gov).

Bamble, Katherine; Jass, Christopher N.; et al; Ice Age Mammals: A Guide for Alberta's Sand and Gravel Industry; Royal Alberta Museum; June 2019; (PDF) ICE AGE MAMMALS: A Guide for Alberta's Sand & Gravel Industry (researchgate.net; Site accessed 9-24-2024.

BioMed Central; A Mammoth Task—sorting out mammoth evolution; Phys.org; May 30, 2011; Site accessed May 24, 2022; A mammoth task -- sorting out mammoth evolution (phys.org).

Burns, James A.; Young, Robert R.; Pleistocene Mammals of the Edmonton Area, Alberta. Part I. The Carnivores; Canadian Journal of Earth Science; Vol. 31, No. 2; Pgs. 393-400; February 01, 1994; (PDF) Pleistocene mammals of the Edmonton area, Alberta. Part I. The carnivores (researchgate.net).

Boeskorov, Gennady G.; Arctic Siberia: refuge of the Mammoth fauna in the Holocene; Quaternary International; 142-143; 2006; Pgs. 119-123; (99+) Arctic Siberia: refuge of the Mammoth fauna in the Holocene | Gennady Boeskorov – Academia.edu.

Carlson, Randall; Site accessed May 24, 2022; Homepage - Randall Carlson.

Churcher, C.S.; The Vertebrate Faunas of Surprise, Mitchell, and Island Bluffs, Near Medicine Hat, Alberta (72L); Geological Survey of Canada; Report of Activities Part A: April to October 1969; Pgs. 158-160; pa_70_1a.pdf (canada.ca) or GEOSCAN Search Results: Fastlink (nrcan.gc.ca).

Dantheman9758; Deviant Art; Site accessed May 24, 2022; Search 'Dantheman9758' on DeviantArt - Discover The Largest Online Art Gallery and Community.

Dvorksy, George; How the Last Woolly Mammoths Met Their Demise on a Remote Arctic Island; Gizmodo; Oct 7, 2019; How the Last Woolly Mammoths Met Their Demise on a Remote Arctic Island (gizmodo.com); Site accessed 2-17-2023

Earth Science; Chapter 13-Glaciers & Glaciation; Site accessed May 5, 22, 2022; https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/earth_science/chapter13.html.

Enk, Jacob; et al; Complete Columbian Mammoth Mitogenome Suggests Interbreeding with Wolly Mammoths; Genome Biology; 12(5):R51; May 31, 2011; Complete Columbian mammoth mitogenome suggests interbreeding with woolly mammoths (nih.gov).

Extinct Western Camel (Camelops hesternus) Fact Sheet; Summary; San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Library; March 30, 2021; Site accessed May 25, 2022; Summary - Extinct Western Camel (Camelops hesternus) Fact Sheet - LibGuides at International Environment Library Consortium.

Firestone, Richard B.; Disappearance of Ice Age Megafauna and the Younger Dryas Impact; Planetary Scinece; July 24, 2019; https://beta.capeia.com/planetary-science/2019/06/03/disappearance-of-ice-age-megafauna-and-the-younger-dryas-impact.

Fyon, Andy; Ice Age Mammals-Woolly Mammoth; Canada (Ontario) Beneath Our Feet; April 6, 2017; Site accessed May 24, 2022; Ice Age Mammals - Woolly Mammoth — Canada (Ontario) Beneath Our Feet (ontariobeneathourfeet.com).

Graham, Russell W.; Belmecheri, Soumaya; et al; Timing and Causes of Mid-Holocene Mammoth Extinction On St Paul Island, Alaska; PNAS; Vol 113, No 33; August 16, 2016; (96) Timing and causes of mid-Holocene mammoth extinction on St. Paul Island, Alaska | Lee Newsom – Academia.edu; Site accessed 2-16-2023

Hansen, Brage Bremset; et al; Reindeer turning maritime: Ice-locked tundra triggers changes in deitary niche utilization; Ecosphere; Vol. 10, Issue 4; Article e02672; April 2019; https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ecs2.2672 or https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ecs2.2672.

Harington, C.R.; The Kyle Mammoth: A late Pleistocene Columbian Mammoth from Souther Saskatchewan, Canada; Quaternary International; Vol. 443, Part A; July 2017; Pgs. 79-87; The Kyle Mammoth: A Late Pleistocene Columbian mammoth from southern Saskatchewan, Canada – ScienceDirect.

Hill, Christopher L.; Pleistocene Mammals of Montana and Their Geologic Context; Montana State University; Bozeman, MT; 2001; (PDF) Pleistocene Mammals of Montana and Their Geologic Context (researchgate.net).

Howard, George; The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis Since 2007--According to Graham Hancock; https://cosmictusk.com/hancock-younger-dryas-impact-hypothesis-since-2007/; The Cosmic Tusk; May 21, 2017.

Howard, George; Bibliography, Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis; https://cosmictusk.com/younger-dryas-impact-hypothesis-bibliography-and-paper-archive/; The Cosmic Tusk; Raleigh, NC.

Ice Age Animals; Yukon Beringia Interpretative Center; Whitehorse, Yukon; Site accessed May 5, 2022; https://www.beringia.com/exhibits/ice-age-animals.

Janssen, Willem; Ice Ae Extinctions Event; Tracing Origins: A Hobby to the Origins of Civilization; January 28, 2019; Site accessed May 5, 2022; Ice Age extinction event – Tracing Origins.

Kenny, Gavin G.; et al; A Late Paleocene Age for Greenland’s Hiawatha Impact Structure; Science Advances; Vol. 8, No. 10; March 9, 2022; https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm2434.

King, Gilbert; Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed; https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-the-buffalo-no-longer-roamed-3067904/ ; Smithsonian Magazine; Washington, DC; July 17, 2012

Kristensen, Todd; Changing Animals: Alberta's Ice Age Megafauna and Wally's Beach; Retroactive; July 13, 2016; Changing Animals: Alberta’s Ice Age Megafauna and Wally’s Beach – RETROactive (albertashistoricplaces.com); Site accessed 9-24-2024.

Jikke and Roselinde; Pleistocene Project; Learn all about the Previous Geological Age; Mammals | Pleistocene Project (wordpress.com).

Kuss, Charles; The Younger Dryas Event a recent climate disruption and extinction event, and how it may relate to past major and minor extinctions events; Southwestian (personal blog); Blogger.com; 2021; SOUTHWESTIAN: THE YOUNGER DRYAS EVENT a recent climate disruption and extinction event, and how it may relate to past major and minor extinction events.

Mammoth vs Mastodon; Diffen; Site accessed May 24, 2022; Mammoth vs Mastodon - Difference and Comparison | Diffen.

Mammut, including Mammut americanum (American mastodon); Prehistoric Wildlife; Site accessed May 5, 2022; http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/m/mammut.html or http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/index.html.

McNeil, Paul E.; et al; Mammoth Steps: an overview of the fauna of Wally's Beach (DhPg-8), a late Pleistocene locality from southwestern Alberta; Working with the Earth-GeoCanada; 2010; Mammoth steps: an overview of the fauna of Wally’s Beach (DhPg-8), a late Pleistocene locality from southwestern Alberta (geoconvention.com); Site accessed 9-24-2024.

Naturewasmetal; The Pleistocene was a time of giants....; Reddit; 2020; Site accessed 5-15-2022; The Pleistocene was a time of giants. Before their mysterious vanishing, the megafauna were in abundance similar to the African savannah today. A mosaic of steppe & taiga was a complex ecosystem; one supported by its keystone species, the woolly mammoth, whose size opened habitat for other species. : Naturewasmetal (reddit.com).

Paul Markwick; Paul’s Palaeo Pages, Cenozoic Palaeogeography; 2021; Site accessed on May 5, 2022; Cenozoic Maps - Paul's Palaeo Pages (palaeogeography.net).

Radiocarbon Dating; Vancouver Island University; 2012; Site accessed May 19, 2022; Radiocarbon dating.pdf (viu.ca).

Reindeer; World Deer; 2022; Site accessed May 27, 2022; Reindeer Facts & Information (Rangifer tarandus) | Learn About Reindeer (worlddeer.org).

Reynolds, Ashley R.; et al; Late Pleistocene Records of Felids from Medicine Hat, Alberta, Including the First Canadian Record of the Sabre-Toothed Cat Smilodon fatalis; Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences; January 22,2019; cjes-2018-0272.pdf (utoronto.ca).

Rogers, Rebekah L.; Slatkin, Montgomery; Excess of Genomic Defects In A Wolly Mammoth On Wrangel Island; PLOS Genttics; March 2, 2017; Excess of genomic defects in a woolly mammoth on Wrangel island (plos.org); Site accessed 2-17-2-23

Rosane, Olivia; Reindeer Numbers Have Fallen by More than Half in 2 Decades; EcoWatch; Dec 13, 2018; Site accessed May 27, 2022; https://www.ecowatch.com/reindeer-population-climate-change-2623281571.html.

Royal Alberta Museum; Mammoths versus Mastodons: what is the difference?; Site accessed May 24, 2022; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcFlCNTNV8s.

Softschools.com; Saber-toothed Tiger Facts; 2020; Site accessed May 5, 2022; Saber-toothed tiger Facts (softschools.com).

Spray, John (Director); Earth Impact Database; Planetary and Space science Centre; University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB; Site accessed 5-17-2022; Earth Impact Database (passc.net).

Stalker, A.M; Ice Age Deposits and Animals From the Southwestern Part of the Great Plains of Canada (Chart); Geological Survey of Canada; Misc Report 31; 1982; GEOSCAN Search Results: Fastlink (nrcan.gc.ca).

Stoffel, Eliann W; The Kyle Mammoth Project: An Archaeological, Paleoecological and Taphonomic Analysis (Masters Theses); Department of Archaeology and Anthropology; University of Saskatchewan; Saskatoon, SK; August 08, 2016; The Kyle Mammoth Project: An Archaeological, Paleoecological and Taphonomic Analysis (usask.ca).

Stoffel, Eliann W.; The Kyle Mammoth Project: An Archaeological, Paleoecological and Taphonomic Analysis (Masters Thesis); Department of Archaeology and Anthropology; University of Saskatoon; Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; 2016; (99+) The Kyle Mammoth Project: An Archaeological, Paleoecological and Taphonomic Analysis | Eliann Stoffel – Academia.edu.

Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy--Major Divisions; 2021; Site accessed May 7, 2022; https://quaternary.stratigraphy.org/major-divisions/.

Waters, Michael R.; et al; Late Pleistocene Horse and Camel Hunting at the Southern Margin of the Ice-free Corridor: Reassessing the Age of Wally’s Beach, Canada; PNAS; Vol. 122, No. 14; April 7, 2017; Pgs. 4263-4267; ptpmcrender.fcgi (europepmc.org).

Wikipedia; Beringia; March 13, 2022; Site accessed May 24, 2022; Beringia – Wikipedia.

Wikipedia: Camelops; Site accessed May 25, 2022; Camelops – Wikipedia.

Wikipedia; Horses in the United States; May 5, 2022; Site accessed May 22, 2022; Horses in the United States – Wikipedia.

Wikipedia; Quaternary Extinction Event; May 6, 2022; Site accessed May 15, 2022; Quaternary extinction event – Wikipedia.

Wikipedia; Radiocarbon Calibration; May 8, 2022; Site accessed May 19, 2022; Radiocarbon calibration – Wikipedia.

Wikipedia; Reindeer; May 23, 2022; Site accessed May 27, 2022; Reindeer – Wikipedia.

Wikipedia; Smilodon; May 31, 2022; Site accessed June 9, 2022; Smilodon – Wikipedia.

Woolly Mammoth Revival-About the Species; Revive & Restore; 2023; About the Woolly Mammoth (reviverestore.org); Site accessed 2-17-2023

Youtube: Shawn Ryan Show; Randell Carlson-Rediscovering Ancient Civilization: SRS# 103; April 1, 2024; Randall Carlson - Rediscovering Ancient Civilizations | SRS #103 (youtube.com); Site accessed 6-29-2024.

Charles Kuss 2022

Updated 04-22-2025

glacial%20geology.png)